Case Study: Online Threat

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

Recently, some clients contacted TorchStone’s protective intelligence team via our Global Security Operations Center and noted they were alarmed to learn their companies were included on a list of targets by the administrator of a white supremacist accelerationist group chat on the Signal messaging service. The clients provided us with a few details and asked for our assessment of the potential threat.

Context

The target list posted to the Signal chat reportedly contained some 270 entities that spanned a wide array of sectors, including houses of worship, media outlets, financial firms, tech companies, defense contractors, government buildings, embassies, and migrant centers, among others. Other posts in the chat where the target list was posted reportedly called for bombing and other attacks against the targets and provided instructions on manufacturing weapons such as Molotov cocktails, bombs, and 3D-printed firearms.

The accelerationist segment of the white supremacist movement is comprised of extremists who believe they can trigger a race war by conducting enough attacks to cause targeted minority groups to respond by attacking whites. The goal is to create a spiral of racial violence that leads to all-out war, the collapse of civilization and the government, and the eventual rise of a white ethnostate.

Many younger accelerationists come from the so-called “siege culture” milieu, but prominent ideologues from various strands of the white supremacist movement have promoted the concept of accelerationism for decades. National Alliance leader William Pierce wrote two books in the 1970s and 1980s, The Turner Diaries and Hunter, that he intended to serve as instruction manuals for launching a race war. Neo-Nazi ideologue James Mason wrote the material contained in the book Siege in a series of newsletters during the 1980s and it was first published as an anthology in 1992, so the ideology behind “siege culture” is by no means new.

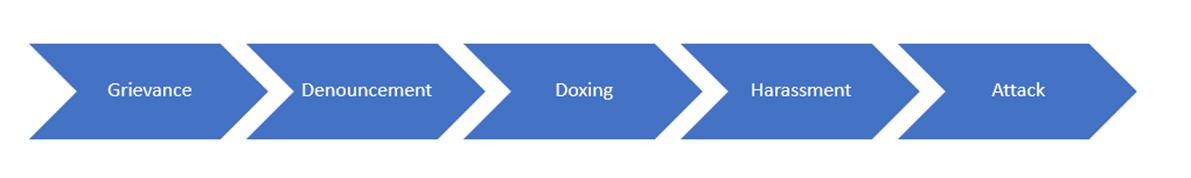

The Social Media Threat Continuum

The posting of the target list to the Signal chat group closely aligns to the leaderless resistance model of terrorism, as well as the social media threat continuum we have developed to help explain the dynamics created when leaderless resistance is applied in the age of smartphones, social media, and messaging applications.

In this case, an extremist influencer—the Signal message group administrator— used his position to articulate the grievances of the “in-group” (white supremacists), identify and denounce enemies of the “in-group” (minorities, the government, corporations), identify specific entities as targets for attack, and then provide adherents with instructions to assist in an attack.

The steps along the continuum in this case actually align very closely with what we have seen jihadist influencers attempt to do through vehicles such as Inspire Magazine or al-Naba Magazine, and in chat groups on Telegram and Signal.

Assessment

The first thing we can conclude is that by publishing the target list, the chat room administrator is signaling that he is not aware of any pending attack plots against any of the listed entities. If he had knowledge of such a plot, it is highly unlikely that he would want to name the target publicly and potentially cause the entity to increase its security—thus making the pending attack more difficult. It is never good to attack with heightened security, and it is even worse if you cause the heightened security yourself by identifying the target in public.

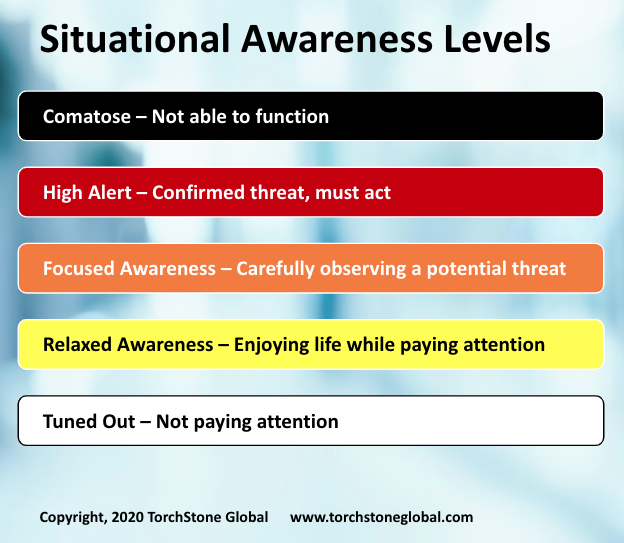

Because of this, the release of the target list is cause for concern but not panic. It does not in any way raise the existing threat level but reminds us of the persistent, low-level threat and the need to maintain an appropriate level of situational awareness—relaxed vigilance, not focused awareness or high alert—unless something is noticed.

Security suffers when people attempt to live in condition orange or red. Adrenalin can be a real asset in an emergency situation, but too much adrenalin can lead to both physical and mental health problems.

Any extremist who was radicalized and operationalized by this chat room, and who then decided to conduct an attack would still be bound by the constraints of the attack cycle and vulnerable to detection as they progress through the cycle.

The leaderless resistance model provides increased safety for the extremist influencers and enhanced operational security for the aspiring attackers. Additionally, social media and messaging apps provide the influencers with a vast array of potential recruits who consume their propaganda – but these benefits come at a significant cost.

First, the extremist influencer does not have the ability to select operatives for an attack. Rather, the operatives are radicalized by the grievance narrative and then self-mobilized. Instead of being able to select the cream of the crop for an attack, extremist influencers are essentially stuck with volunteers. While some grassroots operatives are intelligent and highly capable, most of them tend to lack competence and ability, and many bungle attacks or stumble into sting operations.

Bereft of high-level terrorist tradecraft, these attackers are more likely to focus on soft targets, and to use simple attack methods such as arson, vehicular assault, edged weapon attacks, simple bombings, or armed assaults, using readily available weapons.

Secondly, under this model it is not possible for the extremist influencer to manage and direct the attack cycle of the self-appointed attacker. They have no control over the specific target chosen, the means of attack, or the timing of the attack, which complicates their efforts to exploit the attack for propaganda value.

Another conclusion we can make from the list is that there are simply too many targets on it for the extremist influencer to have any expectation of even a small percentage of them being attacked. The list was so broad that almost any attack by a white supremacist against any target could allow this extremist influencer to claim responsibility. But truth be told, this list was far more aspirational than operational, and the influencer had very little hope of successfully striking all these targets.

Because of this, it is not a stretch to assume the influencer’s real intent in publishing the list was to cause fear and panic among those entities appearing on it. In terms of the social media threat continuum, the list is a form of harassment and intimidation, and it is very important for those entities appearing on the list to fight the urge to panic. A synonym for panic is terror, and practitioners of terrorism will seek to create terror even when they can’t conduct a successful attack. But ideologues who promote terrorism lose a great deal of their power and reach if the people they are targeting refuse to be terrorized.

One other potential objective of publishing the list, or perhaps a secondary objective, was to use it as a “barium meal.” In counterintelligence, a barium meal operation is when an organization intentionally leaks a salacious piece of information to see if there is an infiltrator in their midst. In this case, the white supremacist chat room administrator may have suspected that the group had been infiltrated by government or private sector operatives. This is a valid assumption given the history of white supremacist organizations and cells being infiltrated. After news of the list began to circulate, the chat room administrator now has confirmation that there is an infiltrator in the room.