Exploiting Vulnerabilities in the Attack Cycle

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

In the piece TorchStone Global previously published on understanding the attack cycle, I noted that the most important reason for studying the attack cycle is that it is a useful tool for proactively preventing attacks. It does so by providing a framework to identify behaviors and activities associated with an attack as it is being planned so that tell-tale signs can be detected and the attack thwarted.

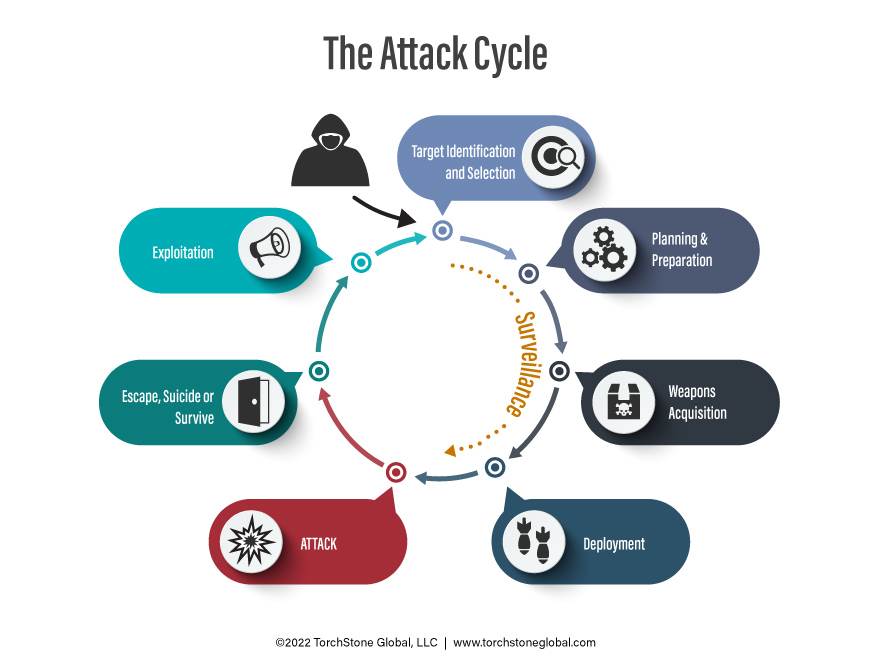

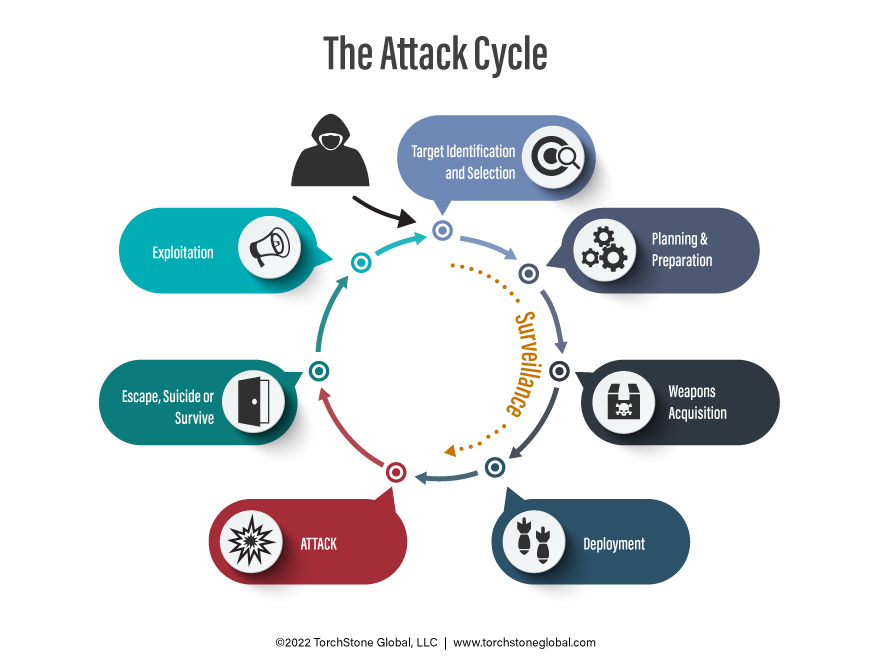

The reason this is possible is that the demands of the attack cycle constrain anyone wishing to conduct an attack. For example, a would-be attacker must identify and select a target, plan the attack and then acquire whatever means of attack (e.g., weapons, cyber, etc.) they choose to use. Furthermore, as they conduct some of these activities, they are vulnerable to detection, either by the authorities, a third-party observer, or the intended victim. For reference, here is how I conceptualize the attack cycle:

While it is possible to thwart an attack at the last second, it is obviously best to detect and take action to interdict a plot before it advances to the attack stage when the attackers are armed, deployed, and ready to strike. Emphasis should therefore be placed on attempting to identify potential attackers earlier in the cycle.

Unless there is an informant inside a group planning an attack or the government manages to intercept communications between plotters, the only way to identify a potential attacker is by observing their actions. This is especially true of a lone actor who has not made a threat to the target and who does not conspire with or communicate with outsiders. In such cases, the earliest point in the attack cycle that the attackers can be identified is while conducting surveillance during the target identification and selection phase. Additional surveillance is often conducted at later stages of the attack cycle, such as in the planning stage and even sometimes during the deployment phase, as the attackers track the target from a known location to the attack site. Each time surveillance is performed, it provides an additional opportunity for the assailants to be identified and the attack to be prevented. Surveillance is also a process whereby the people performing it must expose themselves to observation by the potential target. Because of these factors, surveillance—other than the attack itself—is the activity during which an attacker is most vulnerable to detection. It is thus worth examining surveillance in more detail.

Surveillance

Surveillance, the act of watching someone or something, is far more difficult than most people realize—especially if one desires to remain undetected while doing so. After decades of experience conducting and looking for surveillance, I believe it is an unnatural behavior for most people. Most people are thus poor at surveillance unless they have received training. This is true for criminals, terrorists, and stalkers, as well as for most police officers and federal agents like me. I personally found that the introductory classes in surveillance techniques I received at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center did not really provide me with much in the way of street skills—skills often referred to as surveillance tradecraft. It was only after taking the much more extensive CIA Surveillance Techniques Course that I began to become more adept in the art. Even then, it took me many hours of additional street time to really begin to hone my tradecraft.

Surveillance is as much an art as it is a science. Like learning to play a musical instrument, mastering surveillance tradecraft requires practice in addition to instruction in theory. High-level surveillance teams receive extensive training that includes many hours of practical exercises. Most people don’t receive this level of training or practical experience; they thus tend to possess very little in the way of surveillance tradecraft—and it shows.

It seems counterintuitive that surveillance is essential to the attack cycle but that most attackers are bad at it. Yet the reason hostile actors can operate successfully despite poor surveillance tradecraft is that most targets employ similarly poor situational awareness and are simply not looking for surveillance directed against them. Indeed, during their selection process, attackers will often bypass a potential target who is practicing good situational awareness in favor of a target who is not. I’m going to write in more detail on situational awareness in a later piece, so for now, let’s turn our attention to what poor surveillance looks like.

Watching for Watchers

Perhaps the most common tradecraft mistake people make when they conduct surveillance is exhibiting bad demeanor, meaning that they stick out from the surrounding environment. Practicing proper demeanor while conducting surveillance often runs counter to human nature, which is one of the primary reasons training and practice are needed to create a good surveillance operative. Mastering the art of surveillance is thus predicated on being flexible and learning to display an appropriate demeanor, regardless of the situation.

One part of demeanor is body language. Since surveillance is an unnatural act, people who are performing surveillance feel out of place, awkward, and self-conscious. This causes them to feel what is called the “burn syndrome,” or the feeling that the target has seen them. The feeling of being burned often makes a person conducting surveillance act in an unusual manner. I have seen surveillants quickly turn their head to avoid eye contact with the target, try to hide behind a car, duck into a doorway or bus shelter, and even suddenly raise a newspaper or magazine to hide their faces. Sometimes these behaviors are less obvious, such as a hitch in the surveillant’s step or a slight hesitation in whatever action they are taking at that moment. Through training and practice, surveillance operatives can learn to control themselves as they experience the burn syndrome, but the feeling never really goes away.

Another common demeanor problem is the lack of proper cover for status and action. Cover for status is the persona a surveillance operative adopts, their costume if you will. Common examples include acting as a student, a bike messenger, a businessperson, or a shopper. Obviously, the cover for status must be appropriate for the environment. A man in a business suit attempting to surveil a person on the beach is an example of a bad cover for status. Cover for action tells the story of why a particular character is doing what they are doing. Examples include waiting for a bus, taking a smoke break, window shopping, etc. Cover for action must also be logical and consistent with cover for status. One can’t plausibly stand in front of a retail store pretending to window shop for a half hour.

Employing proper cover for status and cover for action allows the person conducting surveillance to become a part of the environment and seamlessly fit into the subconscious mental snapshot taken by the target going about his or her business. For the most part, however, untrained and inexperienced people conducting surveillance practice little or no cover for action or status. They just lurk and look out of place, as there is no apparent reason for them to be where they are or for doing what they are doing. Consequently, they are not difficult to spot if someone is watching for them, which explains why surveillance creates so much vulnerability for a would-be assailant.

Other Vulnerabilities

During the planning phase, communication between members of the group will often increase, and this increased communication can be picked up by intelligence services. In some cases, this increased communication can even continue after the attack is launched, as was seen during the 2008 Mumbai and 2015 Paris attacks. There can even be an increase in communication in cases involving a lone actor if the lone actor is being radicalized or directed by a facilitator abroad.

Group members may also engage in outside training that can attract attention, such as playing paintball, visiting the firing range, or as was the case with the 9/11 pilots, attending flight schools. This increase in activity may also include travel, money transfers, or even dry runs of the operation.

Another significant vulnerability during the attack cycle is weapons acquisition. This vulnerability is especially pronounced when dealing with inexperienced attackers, who tend to aspire to conduct spectacular attacks that are far beyond their capabilities. In past cases, would-be attackers have decided they wanted to conduct a large vehicle bombing even though they did not have any bomb-making capability themselves. This often leads them to reach out to someone with bomb-making experience, and in many cases, this has led to attackers being caught in law enforcement sting operations when the person they reach out to is an informant or undercover law enforcement officer. In other instances, attackers have blundered into sting operations while seeking to acquire hand grenades, automatic weapons, and even Stinger anti-aircraft missiles.

Even when those plotting attacks have some bomb-making ability, they are still vulnerable while attempting to acquire explosives or chemicals to manufacture improvised explosives or other bomb-making components. The act of manufacturing homemade explosive mixtures often involves acids and other chemicals such as acetone that can create strong fumes. Bomb makers will also often test their homemade explosive mixtures, improvised detonators, and other components, and these tests result in small explosions that can be detected.