Reflections on 9/11 — Twenty Years Later

By TorchStone VP, Scott Stewart

As a member of the team that investigated the 1993 World Trade Center bombing, I was profoundly and personally affected when I watched the twin towers collapse on live television on Sept. 11, 2001, and by the attack on the Pentagon and the fate of United Flight 93.

Many people don’t realize the sheer size of the crater left in the parking garage of the World Trade Center’s parking garage by the large truck bomb that detonated on Feb. 26, 1993, but it was gigantic and stretched several stories up and down from the detonation point.

From my perspective, it is a miracle that only six people died. Had that same bomb been detonated at street level it could have killed scores, if not hundreds of people.

Yet despite the size of this massive bomb, it was unable to cause significant damage to the twin towers.

The time I spent combing for evidence in the crater in the heart of the World Trade Center and then the years of effort I put into helping catch and prosecute those responsible for the attack also gave me a special affinity for the twin towers.

I am sure that my colleagues from the wide array of agencies involved in the 1993 investigation shared those same feelings of disbelief, grief, and shock as we watched the towers collapse into heaps of rubble on the morning of September 11, 2001.

And we were not alone—Americans from all walks of life and across all political persuasions were deeply impacted by the events that September morning.

Things Will Never Be the Same

I can still recall watching television interviews in the wake of the 9/11 attacks in which people of many different backgrounds told reporters that “Things will never be the same again.”

And these statements were not just made by Americans; the spectacular attacks against the symbols of America’s economic, military and political power also made a profound impression on people outside of the United States.

The front page of the French newspaper Le Monde declared on Sept. 12, 2001, “We are all Americans.” This sentiment was shared by citizens and leaders across the globe.

For a while, things did change. Following 9/11, police officers and firefighters again became heroes that were celebrated in many public forums.

New York Police Department and New York Fire Department hats and t-shirts were sold in large numbers and worn by people in cities and states across the country.

In the face of a serious external threat, patriotism soared, and Americans became united.

They were united not only in their fear of the threats of a follow-on attack by al Qaeda but also by their thirst for revenge. Support for the U.S. government and military also soared.

This increase in patriotism and support for law enforcement and the military served to undermine domestic political extremism of all kinds.

Anarchist extremism had grown alarmingly in the United States through the 1990s, and this growth was perhaps best seen by the November 1999 “battle of Seattle,” in which anarchists protesting a meeting of the World Trade Organization fought police and caused significant damage to corporate targets in downtown Seattle.

In May 2001, the Earth Liberation Front conducted an arson attack at the University of Washington’s center for urban horticulture that caused $7 million in damages.

But the 9/11 attacks took much of the air out of the anarchist anti-government, anti-capitalist movement.

In January 2002, the World Economic Forum meeting was moved from Davos, Switzerland, to New York, in a move intended to show solidarity with the city and the United States.

The meeting was remarkable for the lack of protest activity considering how the WEF meetings in Davos, Switzerland in 2000 and 2001 had been marred by significant protest activity.

Right-wing extremism was also impacted by 9/11 after having picked up significant momentum in the mid-to-late 1990s.

The 1996 Oklahoma City Bombing, and Eric Rudolph’s 1996-1998 bombing spree, were followed by a series of white supremacist attacks in summer 1999 that included shooting sprees, murders and synagogue arsons caused it to be labeled it the “Summer of Hate.”

In May of 2000, a Pittsburgh white supremacist went on a shooting spree targeting Jewish, Asian and African Americans in which he killed five.

But following 9/11, the anti-government militia movement and the white supremacist movement decreased dramatically.

Participants on white supremacist message boards began to rail against patriotic Americans for their support of the government.

When the government began to use the so-called “Patriot Act” to prosecute right-wing extremists, theories began to circulate in racist and militia circles about how the 9/11 attacks were conducted by the U.S. government as an excuse to clamp down on domestic extremism in order to impose martial law.

But Some Things Never Changed

For the 20 years since the 9/11 attacks, the United States has been involved in a protracted war against jihadism, that has not only included al Qaeda’s sanctuary in Afghanistan, but also Iraq and scores of other countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

There have been successes in this war, such as the death of Osama bin Laden and the capture of death of most members of the al Qaeda core’s original leadership.

Al Qaeda has also been prevented from conducting another spectacular terrorist attack in the American heartland as they have long threatened.

However, these successes have come at a steep price both in terms of blood and treasure. Two decades of war have cost billions of dollars, the lives of thousands of U.S. and allied military personnel and have stretched the U.S. military thin.

The protracted war against jihadism has also served to stretch the resolve and patience of the American public.

The recent withdrawal from Afghanistan remains popular with most Americans despite the fact that an overwhelming majority of Americans are highly critical of the Biden Administration’s handling of the withdrawal.

This criticism of the government is not surprising.

Over the past decade, Americans have become increasingly polarized while at the same time becoming more distrustful of the government.

Extremist groups from both ends of the political spectrum have capitalized on this environment to rebound in power. They have also been greatly aided in this by the rise of social media.

Twenty years after Americans were unified in the declaration that “we will never be the same,” we are again witnessing an increase in people who hate the police, hate people of other races and religions, and hate each other.

Alarming numbers of Americans are participating in partisan politics in a way that is more extreme and violent than anything America has experienced since the late 1960s and early 1970s.

While 9/11 served as a unifying event, COVID, counter-intuitively, has separated us even more (to our detriment) while also growing mistrust of the government.

Internationally, even America’s allies are again decrying the United States as an out-of-control “cowboy” engaged in mindless military excursions across the globe and maliciously spying on the world—that is until they need U.S. military power and intelligence resources to help them intervene in Libya or help roll back the threat of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq.

Even when America comes to the aid of others, it is clear, however, that the rest of the world no longer feels that “we are all Americans.”

Sadly, the further we have moved away from 9/11, the more the world has reverted back to what it was before that tragic day, and in my opinion, certainly not for the better.

I just hope that the American people don’t need to suffer another massive tragedy to once again draw them back together as one—E Pluribus Unum.

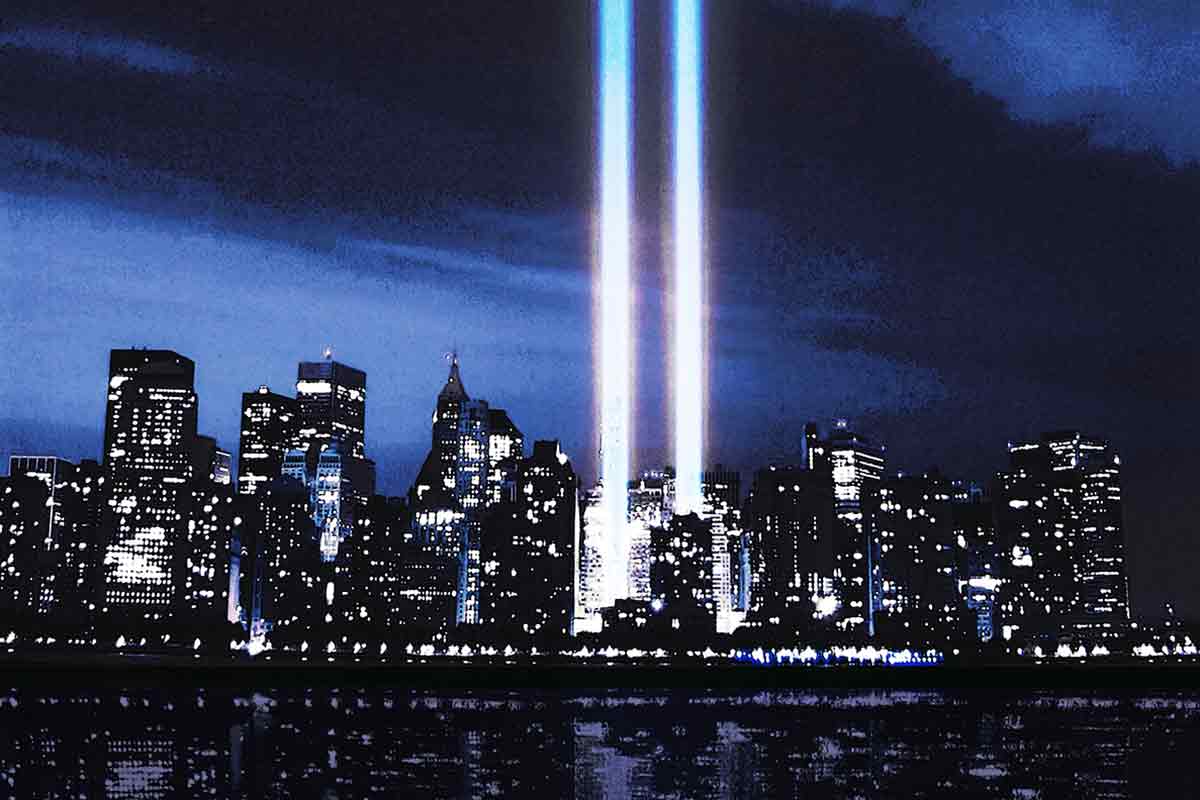

The country and the world may have moved on from 9/11, but when I gaze at the Manhattan skyline today, there is a hole in my heart where the twin towers used to stand.